Overview

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a powerful molecular biology technique used to amplify specific segments of DNA. It allows scientists to make multiple copies of a specific DNA sequence from a tiny amount of starting material. Like a digital photocopier, it enables researchers to amplify DNA segments exponentially, making it easier to analyze and study genetic material. PCR is instrumental in various research and diagnostic applications, helping researchers identify and analyze genes responsible for specific traits or diseases, study genetic variations, detect infectious agents, and conduct forensic investigations. It also aids in cloning DNA fragments and preparing samples for sequencing.

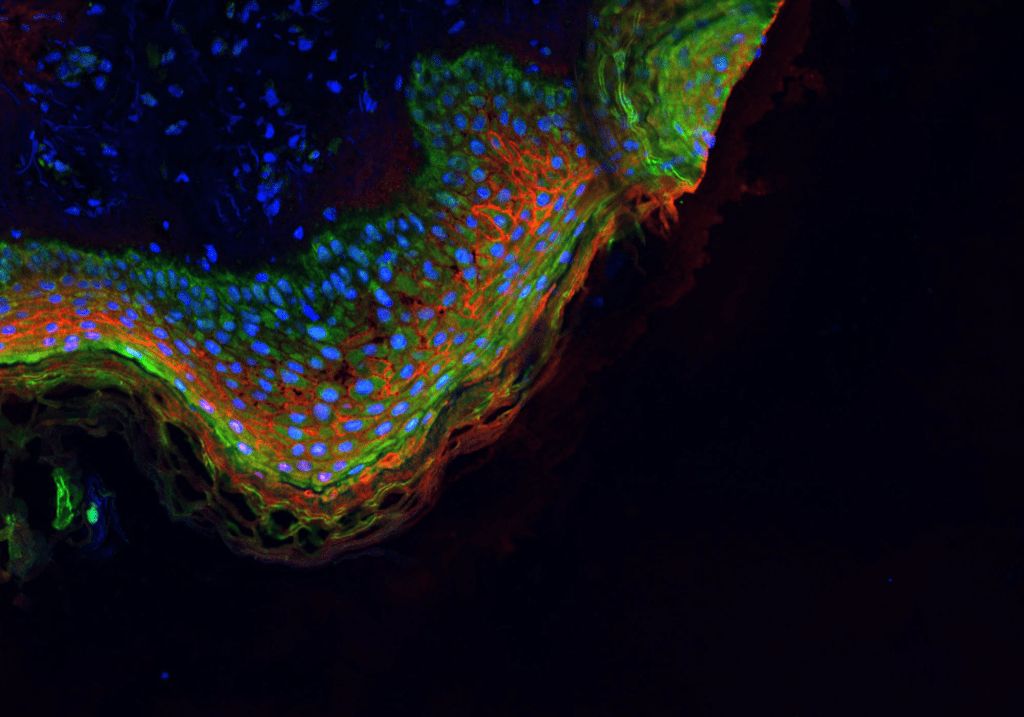

PCR is widely used in genetics, genomics, molecular biology, and biotechnology research. It plays a crucial role in fields such as genetic disease research, microbiology, evolutionary studies, and environmental monitoring.

Materials Required for PCR:

To perform a basic PCR, you’ll need a few key components:

- DNA Template: The DNA containing the target sequence to be amplified. Primers: Short DNA sequences that flank the target region and serve as starting points for DNA synthesis.

- DNA Polymerase: An enzyme responsible for adding nucleotides and building the new DNA strand.

- Nucleotides: The building blocks of DNA (A, T, C, G) required for DNA synthesis. Buffer Solution: Providing the optimal environment for the PCR reaction.

- Thermal Cycler: The PCR machine that automates the temperature changes needed during the reaction.

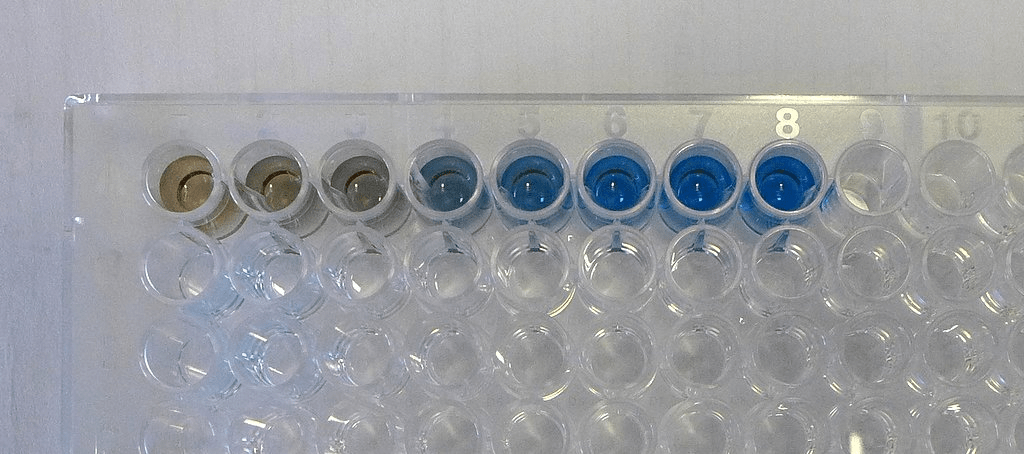

- Reaction Tubes: Small, thin-walled tubes where the PCR reaction takes place.

Basic Step-by-Step PCR Protocol:

Here’s a simplified outline of the PCR process:

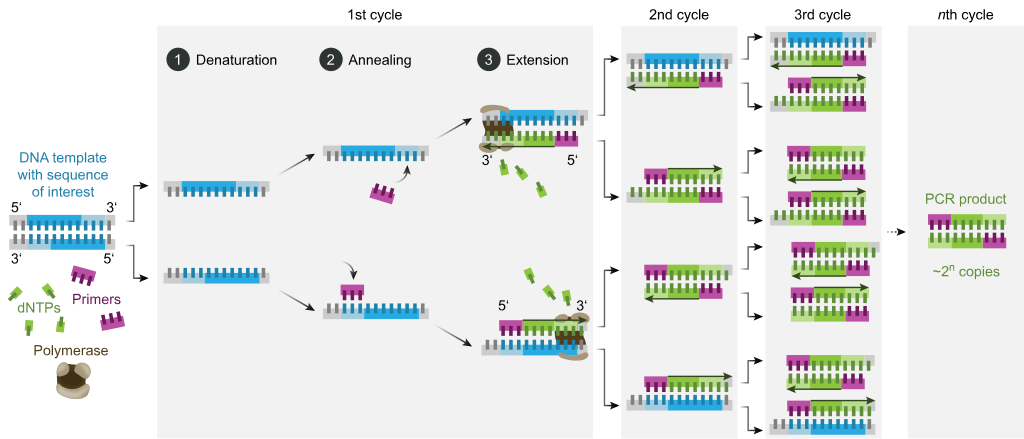

Denaturation: The reaction begins with heating the mixture to a high temperature (e.g., 94-98°C) to denature the double-stranded DNA, separating it into two single strands.

Annealing: The mixture is cooled to a lower temperature (e.g., 50-65°C) to allow the primers to anneal (bind) to their complementary sequences on each DNA strand.

Extension: The temperature is raised to an optimal range for the DNA polymerase (e.g., 68-72°C), which adds nucleotides to the primers, synthesizing new DNA strands.

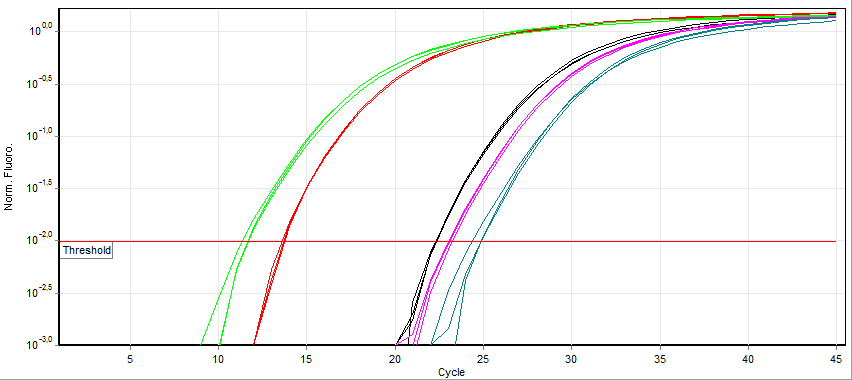

Repeat: Steps 1-3 are repeated in cycles, typically 20-40 times, which leads to an exponential increase in the number of DNA copies of the target region.

Final Extension: After the last cycle, the reaction is held at the extension temperature for a short period to ensure completion of any partial DNA strands.

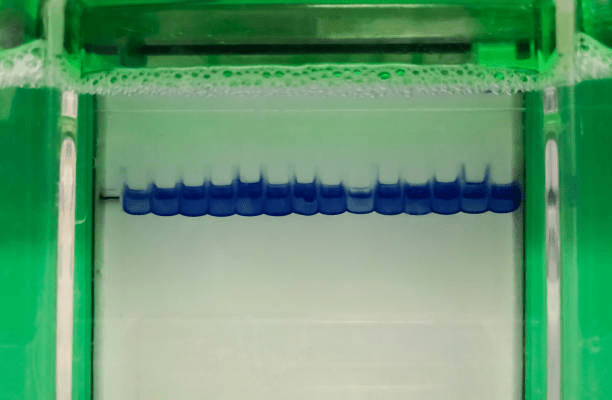

That’s it! Once the PCR is complete, you’ll have a substantial amount of amplified DNA, ready for analysis through gel electrophoresis, sequencing, or other downstream applications.